Shawnee Tribe

Updated: January 13, 2015 |

Alabama,

Kansas,

Kentucky,

Maryland,

Missouri,

Native American,

Ohio,

Pennsylvania,

South Carolina,

Tennessee,

Texas,

Virginia

Shawnee Indians (from

shawŭn, ‘south’;

shawŭnogi,

‘southerners.’ ). Formerly a leading tribe of South Carolina,

Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. By reason of the indefinite character

of their name, their wandering habits, their connection with other

tribes, and because of their interior position away from the traveled

routes of early days, the Shawnee were long a stumbling block in the way

of investigators. Attempts have been made to identify them with the

Massawomec of Smith, the

Erie

of the early Jesuits, and the Andaste of a somewhat later period, while

it has also been claimed that they originally formed one tribe with the

Sauk and

Foxes.

None of these theories, however, rests upon sound evidence, and all

have been abandoned. Linguistically the Shawnee belongs to the group of

Central Algonquian dialects, and is very closely related to

Sauk–

Fox.

The name “Savanoos,” applied by the early Dutch writers to the Indians

living upon the north bank of Delaware river, in New Jersey, did not

refer to the Shawnee, and was evidently not a proper tribal designation,

but merely the collective term, “southerners,” for those tribes

southward from Manhattan island, just as Wappanoos, “easterners,” was

the collective term for those living toward the east. Evelin, who wrote

about 1646, gives the names of the different small bands in the south

part of New Jersey, while Ruttenber names those in the north, but

neither mentions the Shawnee.

Shawnee History

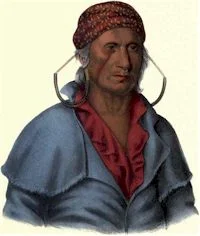

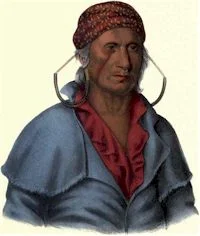

Payta Kootha, Shawanoe Warrior (Shawnee)

Flying Clouds or Captain Reed

The tradition of the

Delawares, as embodied in the

Walam Olum, makes themselves, the Shawnee, and the

Nanticoke, originally one people, the separation having taken place after the traditional expulsion of the Talligewi (

Cherokee)

from the north, it being stated that the Shawnee went south. Beyond

this it is useless to theorize on the origin of the Shawnee or to strive

to assign them any earlier location than that in which they were first

known and where their oldest traditions place them in the Cumberland

basin in Tennessee, with an outlying colony on the middle Savannah in

South Carolina. In this position, as their name may imply, they were the

southern advance guard of the

Algonquian stock.

Their real history begins in 1669-70. They were then living in two

bodies at a considerable distance apart, and these two divisions were

not fully united until nearly a century later, when the tribe settled in

Ohio. The attempt to reconcile conflicting statements without a

knowledge of this fact has occasioned much of the confusion in regard to

the Shawnee. The apparent anomaly of a tribe living in two divisions at

such a distance from each other is explained when we remember that the

intervening territory was occupied by the

Cherokee,

who were at that time the friends of the Shawnee. The evidence afforded

by the mounds shows that the two tribes lived together for a

considerable period, both in South Carolina and in Tennessee, and it is a

matter of history that the

Cherokee

claimed the country vacated by the Shawnee in both states after the

removal of the latter to the north. It is quite possible that the

Cherokee invited the Shawnee to settle upon their eastern frontier in order to serve as a barrier against the attacks of the

Catawba

and other enemies in that direction. No such necessity existed for

protection on their northwestern frontier. The earliest notices of the

Carolina Shawnee represent them as a warlike tribe, the enemies of the

Catawba and others, who were also the enemies of the

Cherokee. In Ramsey’s Annals of Tennessee is the statement, made by a

Cherokee chief in 1772, that 100 years previously the Shawnee, by permission of the

Cherokee, removed from Savannah river to the Cumberland, but were afterward driven out by the

Cherokee, aided by the

Chickasaw,

in consequence of a quarrel with the former tribe. While this tradition

does not agree with the chronological order of Shawnee occupancy in the

two regions, as borne out by historical evidence, it furnishes

additional proof that the Shawnee occupied territory upon both rivers,

and that this occupancy was by permission of the

Cherokee.

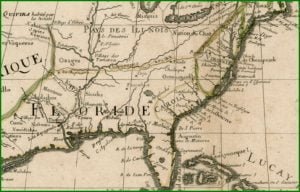

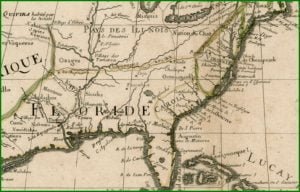

De

l’Isle’s map of 1700 places the “Ontouagannha.” which here means the

Shawnee, on the headwaters of the Santee and Pedee rivers in South

Carolina, while the “Chiouonons” are located on the lower Tennessee

river.

De l’Isle’s map of 1700 places the “Ontouagannha.” which here means

the Shawnee, on the headwaters of the Santee and Pedee rivers in South

Carolina, while the “Chiouonons” are located on the lower Tennessee

river. Senex’s map of 1710 locates a part of the “Chaouenons” on the

headwaters of a stream in South Carolina, but seems to place the main

body on the Tennessee. Moll’s map of 1720 has “Savannah Old Settlement”

at the mouth of the Cumberland , showing that the term Savannah was sometimes applied to the Western as well as to the eastern band.

The Shawnee of South Carolina, who included the Piqua and

Hathawekela

divisions of the tribe, were known to the early settlers of that state

as Savannahs, that being nearly the form of the name in use among the

neighboring

Muskhogean tribes. A good deal of confusion has arisen from the fact that the

Yuchi and

Yamasee,

in the same neighborhood, were sometimes also spoken of as Savannah

Indians. Bartram and Gallatin particularly are confused upon this point,

although, as is hardly necessary to state, the tribes are entirely

distinct. Their principal village, known as Savannah Town, was on

Savannah river, nearly opposite the present Augusta, Ga. According to a

writer of 1740

it was at New Windsor, on the north bank of Savannah river, 7 miles

below Augusta. It was an important trading point, and Ft Moore was

afterward built upon the site. The Savannah river takes its name from

this tribe, as appears from the statement of Adair, who mentions the

“Savannah river, so termed on account of the Shawano Indians having

formerly lived there,” plainly showing that the two names are synonyms

for the same tribe. Gallatin says that the name of the river is of

Spanish origin, by which he probably means that it refers to “savanas,”

or prairies, but as almost all the large rivers of the Atlantic slope

bore the Indian names of the tribes upon their banks, it is not likely

that this river is an exception, or that a Spanish name would have been

retained in an English colony. In 1670, when South Carolina was first

settled, the Savannah were one of the principal tribes southward from

Ashley river. About 10 years later they drove hack the Westo, identified

by Swanton as the

Yuchi,

who had just previously nearly destroyed the infant settlements in a

short but bloody war. The Savannah seem to have remained at peace with

the whites, and in 1695, according to Gov. Archdale, were “good friends

and useful neighbors of the English.” By a comparison of Gallatin’s

paragraph with Lawson’s statements from which he quotes, it will be seen that he has misinterpreted the earlier author, as well as misquoted the tribal forms.

Senex’s

map of 1710 locates a part of the “Chaouenons” on the headwaters of a

stream in South Carolina, but seems to place the main body on the

Tennessee.

Lawson traveled through Carolina in 1701, and in 1709 published his

account, which has passed through several reprints, the last being in

1860. He mentions the “Savannas” twice, and it is to be noted that in

each place he calls them by the same name, which, however, is not the

same as any one of the three forms used by Gallatin in referring to the

same passages. Lawson first mentions them in connection with the

Congaree as the “Savannas, a famous, warlike, friendly nation of

Indians, living to the south end of Ashley river.” In another place he

speaks of “the Savanna Indians, who formerly lived on the banks of the

Messiasippi, and removed thence to the head of one of the rivers of

South Carolina, since which, for some dislike, most of them are removed

to live in the quarters of the

Iroquois or Sinnagars [

Seneca],

which are on the heads of the rivers that disgorge themselves into the

bay of Chesapeak.” This is a definite statement, plainly referring to

one and the same tribe, and agrees with what is known of the Shawnee.

On De l’Isle’s map, also, we find the Savannah river called “R. des

Chouanons,” with the “Chaouanons” located upon both banks in its middle

course. As to Gallatin’s statement that the name of the Savannahs is

dropped after Lawson’s mention in 1701, we learn from numerous

references, from old records, in Logan’s Upper South Carolina, published

after Gallatin’s time, that all through the period of the French and

Indian war, 50 years after Lawson wrote, the “Savannahs” were constantly

making inroads on the Carolina frontier, even to the vicinity of

Charleston. They are described as “northern savages” and friends of the

Cherokee,

and are undoubtedly the Shawnee. In 1749 Adair, while crossing the

middle of Georgia, fell in with a strong party of “the French Shawano,”

who were on their way, under

Cherokee guidance, to attack the English traders near Augusta. After committing some depredations they escaped to the

Cherokee.

In another place he speaks of a party of “Shawano Indians,” who, at the

instigation of the French, had attacked a frontier settlement of

Carolina, but had been taken and imprisoned. Through a reference by

Logan it is found that these prisoners are called Savannahs in the

records of that period. In 1791 Swan mentions the “Savannas” town among

the Creeks, occupied by “Shawanese refugees.”

Having shown that the Savannah and the Shawnee are the same tribe, it

remains to be seen why and when they removed from South Carolina to the

north. The removal was probably owing to dissatisfaction with the

English setters, who seem to have favored the

Catawba

at the expense of the Shawnee. Adair, speaking of the latter tribe,

says they had formerly lived on the Savannah river, “till by our foolish

measures they were forced to withdraw northward in defense of their,

freedom.” In another place he says, “by our own misconduct we twice lost

the Shawano Indians, who have since proved very hurtful to our colonies

in general.” The first loss referred to is probably the withdrawal of

the Shawnee to the north, and the second is evidently their alliance

with the French in consequence of the encroachments of the English in

Pennsylvania.

Their removal from South Carolina was gradual, beginning about 1677

and continuing at intervals through a period of more than 30 years. The

ancient Shawnee villages formerly on the sites of Winchester, Virginia,

and Oldtown, near Cumberland, Maryland, were built and occupied probably

during this migration. It was due mainly to their losses at the hands

of the

Catawba,

the allies of the English, that they were forced to abandon their

country on the Savannah; but after the reunion of the tribe in the north

they pursued their old enemies with unrelenting vengeance until the

Catawba

were almost exterminated. The hatred cherished by the Shawnee toward

the English is shown by their boast in the Revolution that they had

killed more of that nation than had any other tribe.

The first Shawnee seem to have removed from South Carolina in 1677 or

1678, when, according to Drake, about 70 families established

themselves on the Susquehanna adjoining the Conestoga in Lancaster

County, Pennsylvania, at the mouth of Pequea creek. Their village was

called Pequea, a form of Piqua. The Assiwikales (

Hathawekela)

were a part of the later migration. This, together with the absence of

the Shawnee names Chillicothe and Mequachake east of the Alleghanies,

would seem to show that the Carolina portion of the tribe belonged to

the first named divisions. The chief of Pequea was Wapatha, or Opessah,

who made a treaty with Penn at Philadelphia in 1701, and more than 50

years afterward the Shawnee, then in Ohio, still preserved a copy of

this treaty. There is no proof that they had a part in Penn’s first

treaty in 1682.

In 1694, by invitation of the

Delawares and their allies, another large party came from the south probably from Carolina and settled with the

Munsee

on the Delaware, the main body fixing themselves at the mouth of Lehigh

river, near the present Easton, Pennsylvania, while some went as far

down as the Schuylkill. This party is said to have numbered about 700,

and they were several months on the journey. Permission to settle on the

Delaware was granted by the Colonial government on condition of their

making peace with the

Iroquois, who then received them as “brothers,” while the

Delawares acknowledged them as their “second sons,” i. e. grandsons. The Shawnee to-day refer to the

Delawares as their grandfathers. From this it is evident that the Shawnee were never conquered by the

Iroquois, and, in fact, we find the western band a few years previously assisting the

Miami against the latter. As the

Iroquois, however, had conquered the lands of the

Conestoga and

Delawares,

on which the Shawnee settled, the former still claimed the prior right

of domain. Another large part of the Shawnee probably left South

Carolina about 1707, as appears from a statement made by Evans in that

year ,

which shows that they were then hard pressed in the south. He says:

“During our abode at Pequehan [Pequea] several of the Shaonois Indians

from ye southward came to settle here, and were admitted so to do by

Opessah, with the governor’s consent, at the same time an Indian, from a

Shaonois town near Carolina came in and gave an account that four

hundred and fifty of the flat-headed Indians [

Catawba]

had besieged them, and that in all probability the same was taken.

Bezallion informed the governor that the Shaonois of Carolina he was

told had killed several Christians; whereupon the government of that

province raised the said flat-headed Indians, and joined some Christians

to them, besieged and have taken, as it is thought, the said Shaonois

town.” Those who escaped probably fled to the north and joined their

kindred in Pennsylvania. In 1708 Gov. Johnson, of South Carolina,

reported the “Savannahs” on Savannah river as occupying 3 villages and

numbering about 150 men .

In 1715 the “Savanos” still in Carolina were reported to live 150 miles

northwest of Charleston, and still to occupy 3 villages, but with only

233 inhabitants in all.

The

Yuchi and

Yamasee were also then in the same neighborhood .

A part of those who had come from the south in 1694 had joined the

Mahican

and become a part of that tribe. Those who had settled on the Delaware,

after remaining there some years, removed to the Wyoming valley on the

Susquehanna and established themselves in a village on the west bank

near the present Wyoming, Pennsylvania. It is probable that they were

joined here by that part of the tribe which had settled at Pequea, which

was abandoned about 1730. When the

Delawares and

Munsee

were forced to leave the Delaware river in 1742 they also moved over to

the Wyoming valley, then in possession of the Shawnee, and built a

village on the east bank of the river opposite that occupied by the

latter tribe. In 1740 the Quakers began work among the Shawnee at

Wyoming and were followed two years later by the Moravian Zinzendorf. As

a result of this missionary labor the Shawnee on the Susquehanna

remained neutral for some time during the French and Indian war, which

began in 1754, while their brethren on the Ohio were active allies of

the French. About the year 1755 or 1756, in consequence of a quarrel

with the

Delawares,

said to have been caused by a childish dispute over a grasshopper, the

Shawnee abandoned the Susquehanna and joined the rest of their tribe on

the upper waters of the Ohio, where they soon became allies of the

French. Some of the eastern Shawnee had already joined those on the

Ohio, probably in small parties and at different times, for in the

report of the Albany congress of 1754 it is found that some of that

tribe had removed from Pennsylvania to the Ohio about 30 years

previously, and in 1735 a Shawnee band known as Shaweygria

(Hathawekela), consisting of about 40 families, described as living with

the other Shawnee on Allegheny river, refused to return to the

Susquehanna at the solicitation of the

Delawares and

Iroquois.

The only clue in regard to the number of these eastern Shawnee is

Drake’s statement that in 1732 there were 700 Indian warriors in

Pennsylvania, of whom half were Shawnee from the south. This would give

them a total population of about 1,200, which is probably too high,

unless those on the Ohio are included in the estimate.

Having shown the identity of the Savannah with the Shawnee, and

followed their wanderings from Savannah river to the Ohio during a

period of about 80 years, it remains to trace the history of the other,

and apparently more numerous, division upon the Cumberland, who preceded

the Carolina band in the region of the upper Ohio river, and seem never

to have crossed the Alleghanies to the eastward. These western Shawnee

may possibly be the people mentioned in the Jesuit Relation of 1648,

under the name of “Ouchaouanag,” in connection with the

Mascoutens,

who lived in northern Illinois. In the Relation of 1670 we find the

“Chaouanon” mentioned as having visited the Illinois the preceding year,

and they are described as living some distance to the south east of the

latter. From this period until their removal to the north they are

frequently mentioned by the French writers, sometimes under some form of

the collective

Iroquois

name Toagenha, but generally under their Algonquian name Chaouanon. La

Harpe, about 1715, called them Tongarois, another form of Toagenha. All

these writers concur in the statement that they lived upon a large

southern branch of the Ohio, at no great distance east of the

Mississippi. This was the Cumberland river of Tennessee and Kentucky,

which is called the River of the Shawnee on all the old maps down to

about the year 1770.

When the French traders first came into the region the Shawnee had

their principal village on that river near the present Nashville,

Tennessee. They seem also to have ranged northeastward to Kentucky river

and southward to the Tennessee. It will thus be seen that they were not

isolated from the great body of the

Algonquian tribes, as has frequently been represented to have been the case, but simply occupied an interior position, adjoining the kindred

Illinois and

Miami,

with whom they kept up constant communication. As previously mentioned,

the early maps plainly distinguish these Shawnee on the Cumberland from

the other division of the tribe on Savannah river.

These western Shawnee are mentioned about the year 1672 as being harassed by the

Iroquois, and also as allies and neighbors of the Andaste, or

Conestoga, who were themselves at war with the

Iroquois.

As the Andaste were then incorrectly supposed to live on the upper

waters of the Ohio river, the Shawnee would naturally be considered

their neighbors. The two tribes were probably in alliance against the

Iroquois,

as we find that when the first body of Shawnee removed from South

Carolina to Pennsylvania, about 1678, they settled adjoining the

Conestoga,

and when another part of the same tribe desired to remove to the

Delaware in 1694 permission was granted on condition that they make

peace with the

Iroquois. Again, in 1684, the

Iroquois

justified their attacks on the Miami by asserting that the latter had

invited the Satanas (Shawnee) into their country to make war upon the

Iroquois.

This is the first historic mention of the Shawnee evidently the western

division in the country north of the Ohio river. As the Cumberland

region was out of the usual course of exploration and settlement, but

few notices of the western Shawnee are found until 1714, when the French

trader Charleville established himself among them near the present

Nashville. They were then gradually leaving the country in small bodies

in consequence of a war with the

Cherokee, their former allies, who were assisted by the

Chickasaw. From the statement of Iberville in 1702

it seems that this was due to the latter’s efforts to bring them more

closely under French influence. It is impossible now to learn the cause

of the war between the Shawnee and the

Cherokee. It probably did not begin until after 1707, the year of the final expulsion of the Shawnee from South Carolina by the

Catawba, as there is no evidence to show that the

Cherokee took part in that struggle. From Shawnee tradition the quarrel with the

Chickasaw would seem to be of older date. After the reunion of the Shawnee in the north they secured the alliance of the

Delawares, and the two tribes turned against the

Cherokee

until the latter were compelled to ask peace, when the old friendship

was renewed. Soon after the coming of Charleville, in 1714, the Shawnee

finally abandoned the Cumberland valley, being pursued to the last

moment by the

Chickasaw. In a council held at Philadelphia in 1715 with the Shawnee and

Delawares,

the former, “who live at a great distance,” asked the friendship of the

Pennsylvania government. These are evidently the same who about this

time were driven from their home on Cumberland river.

Moll’s

map of 1720 has “Savannah Old Settlement” at the mouth of the

Cumberland, showing that the term Savannah was sometimes applied to the

Western as well as to the eastern band.

On Moll’s map of 1720 we find this region marked as occupied by the

Cherokee,

while “Savannah Old Settlement” is placed at the mouth of the

Cumberland, indicating that the removal of the Shawnee had then been

completed. They stopped for some time at various points in Kentucky, and

perhaps also at Shawneetown, Ill., but finally, about the year 1730,

collected along the north bank of the Ohio river, in Ohio and

Pennsylvania, extending from the Allegheny down to the Scioto. Sawcunk,

Logstown, and Lowertown were probably built about this time. The land

thus occupied was claimed by the

Wyandot,

who granted permission to the Shawnee to settle upon it, and many years

afterward threatened to dispossess them if they continued hostilities

against the United States. They probably wandered for some time in

Kentucky, which was practically a part of their own territory and not

occupied by any other tribe. Blackhoof (Catahecassa), one of their most

celebrated chiefs, was born during this sojourn in a village near the

present Winchester, Kentucky. Down to the

treaty of Greenville, in 1795,

Kentucky was the favorite hunting ground of the tribe. In 1748 the

Shawnee on the Ohio were estimated to number 162 warriors or about 600

souls. A few years later they were joined by their kindred from the

Susquehanna, and the two bands were united for the first time in

history. There is no evidence that the western band, as a body, ever

crossed to the east side of the mountains. The nature of the country and

the fear of the

Catawba

would seem to have forbidden such a movement, aside from the fact that

their eastern brethren were already beginning to feel the pressure of

advancing civilization. The most natural line of migration was the

direct route to the upper Ohio, where they had the protection of the

Wyandot and

Miami, and were within easy reach of the French.

For a long time an intimate connection existed between the

Creeks and the Shawnee, and a body of the latter, under the name of Sawanogi, was permanently incorporated with the

Creeks. These may have been the ones mentioned by Pénicaut as living in the vicinity of Mobile about 1720. Bartram , in 1773, mentioned this band among the

Creeks

and spoke of the resemblance of their language to that of the Shawnee,

without knowing that they were a part of the same tribe. The war in the

northwest after the close of the Revolution drove still more of the

Shawnee to take refuge with the

Creeks. In 1791 they had 4 villages in the

Creek country, near the site of Montgomery, Alabama, the principal being Sawanogi. A great many also joined the hostile

Cherokee about the same time. As these villages are not named in the list of

Creek towns in 1832

it is possible that their inhabitants may have joined the rest of their

tribe in the west before that period. There is no good evidence for the

assertion by some writers that the Suwanee in Florida took its name

from a band of Shawnee once settled upon its banks.

The

view from Prophet’s Rock, a stone outcropping in rural Tippecanoe

County, Indiana near Battle Ground. The Shawnee leader Tenskwatawa (“The

Prophet”), brother of Tecumseh, sang from this site to encourage his

fellow warriors during the fight against William Henry Harrison’s

soldiers at the Battle of Tippecanoe, November 7, 1811. Photo looks

southeast across Prophet’s Rock Road toward Burnett’s Creek and the

battlefield site beyond.

The history of the Shawnee after their reunion on the Ohio is well

known as a part of the history of the Northwest territory, and may be

dismissed with brief notice. For a period of 40 years from the beginning

of the

French and Indian war to the

treaty of Greenville in 1795

they were almost constantly at war with the English or the Americans,

and distinguished themselves as the most hostile tribe in that region.

Most of the expeditions sent across the Ohio during the Revolutionary

period were directed against the Shawnee, and most of the destruction on

the Kentucky frontier was the work of the same tribe. When driven back

from the Scioto they retreated to the head of the Miami river, from

which the

Miami

had withdrawn some years before. After the Revolution, finding

themselves left without the assistance of the British, large numbers

joined the hostile

Cherokee and

Creeks

in the south, while a considerable body accepted the invitation of the

Spanish government in 1793 and settled, together with some

Delawares,

on a tract near Cape Girardeau, Missouri, between the Mississippi and

the Whitewater rivers, in what was then Spanish territory. Wayne’s

victory, followed by the

treaty of Greenville in 1795,

put an end to the long war in the Ohio valley. The Shawnee were obliged

to give up their territory on the Miami in Ohio, and retired to the

headwaters of the Auglaize. The more hostile part of the tribe crossed

the Mississippi and joined those living at Cape Girardeau. In 1798 a

part of those in Ohio settled on White River in Indiana, by invitation

of the

Delawares. A few years later a Shawnee medicine-man,

Tenskwatawa, known as

The Prophet, the brother of the celebrated

Tecumseh,

began to preach a new doctrine among the various tribes of that region.

His followers rapidly increased and established themselves in a village

at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River in Indiana. It soon became evident

that his intentions were hostile, and a force was sent against him

under Gen. Harrison in 1811, resulting in the destruction of the village

and the total defeat of the Indians in the decisive battle of

Tippecanoe.

Tecumseh was among the

Creeks

at the time, endeavoring to secure their aid against the United States,

and returned in time to take command of the northwest tribes in the

British interest in the

War of 1812. The Shawnee in Missouri, who formed about half of the tribe, are said to have had no part in this struggle. By the death of

Tecumseh in this war the spirit of the Indian tribes was broken, and most of them accepted terms of peace soon after. The

Shawnee in Missouri sold their lands in 1825

and removed to a reservation in Kansas. A large part of them had

previously gone to Texas, where they settled on the headwaters of the

Sabine river, and remained there until driven out about 1839 (see

Cherokee). The Shawnee of Ohio

sold their remaining lands at Wapakoneta and Hog Creek in 1831, and joined those in Kansas. The mixed band of

Seneca and Shawnee at Lewistown, Ohio, also removed to Kansas about the same time.

A large part of the tribe left Kansas about 1845 and settled on

Canadian river, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), where they are now known as

Absentee Shawnee. In 1867 the Shawnee living with the

Seneca

removed also from Kansas to the Territory and are now known as Eastern

Shawnee. In 1869, by inter-tribal agreement, the main body became

incorporated with the

Cherokee Nation

in the present Oklahoma, where they are now residing. Those known as

Black Bob’s band refused to remove from Kansas with the others, but have

since joined them.

For Further Study

The following articles and manuscripts will shed additional light on the Shawnee as both an ethnological study, and as a people.

- Shawnee Indians – Swanton

- Creek Confederacy – Swanton

- Shawnee Treaties

- Treaty of January 31, 1786

- Treaty of August 3, 1795

- Treaty of June 7, 1803

- Treaty of July 4, 1805

- Treaty of November 25, 1808

- Treaty of July 22, 1814

- Treaty of September 8, 1815

- Treaty of September 29, 1817

- Treaty of September 17, 1818

- Treaty of November 7, 1825

- Treaty of July 20, 1831

- Treaty of August 8, 1831

- Treaty of October 26, 1832

- Treaty of December 29, 1832

- Treaty of May 10, 1854

- Agreement of September 13, 1865

- Treaty of February 23, 1867

- Shawnee Tribal Locations

- Indian Missions of Middle Atlantic States

- Native American Land Patents

- Wyandot and Shawnee Indian Lands

- Free US Indian Census Schedules 1885-1940

- Quapaw Agency

- Eastern Shawnee

- Seneca Agency

https://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/shawnee-tribe.htm

Piqua Shawnee

piquashawnee.com